Represented Artists

Featured Artists

-

David Barker

-

Samuel John Lamorna Birch

-

Anthony Blake

-

Katharine Church

-

Vera Cummings

-

Sir William Russell Flint

-

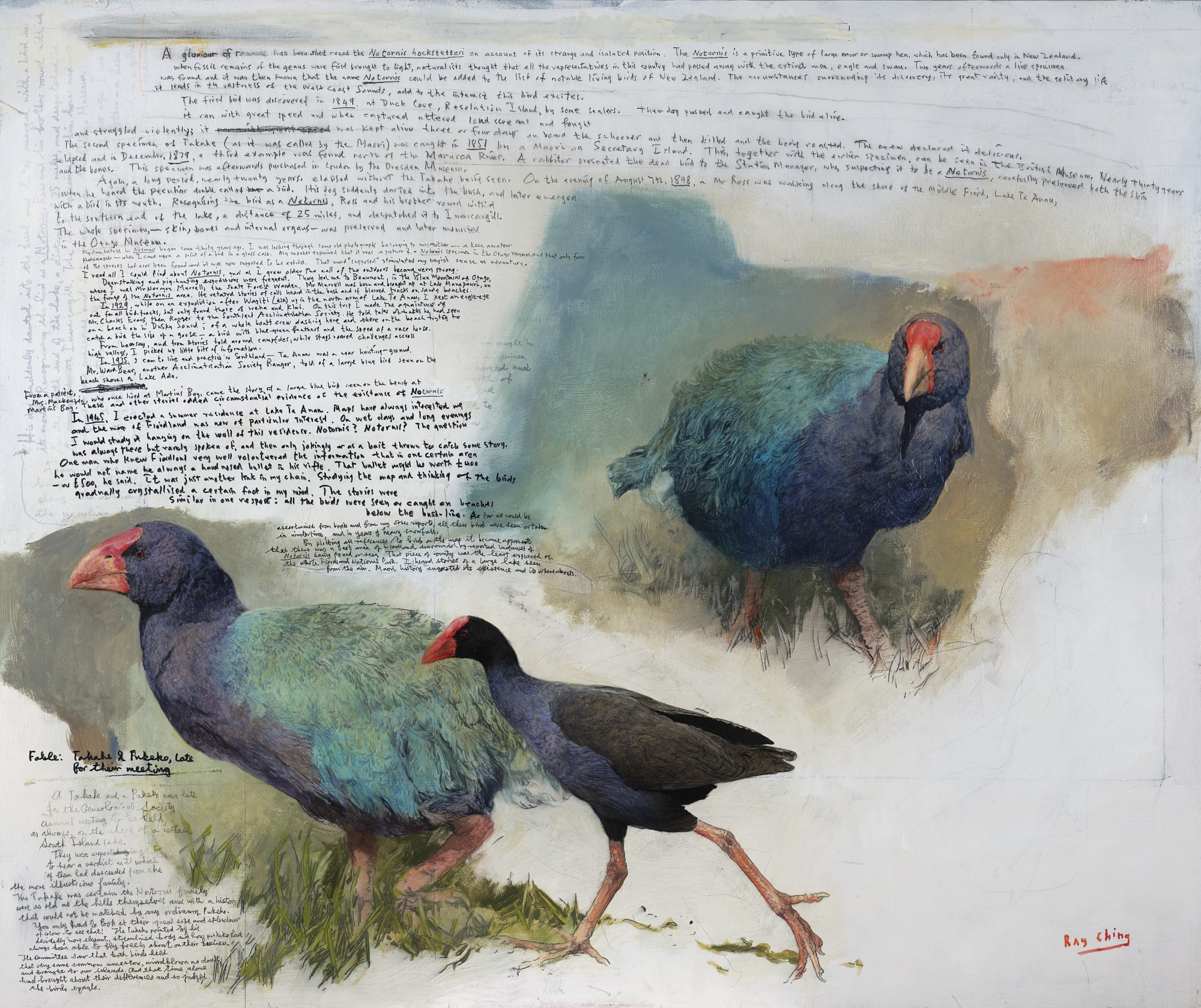

Charles Goldie

-

Patrick Hayman

-

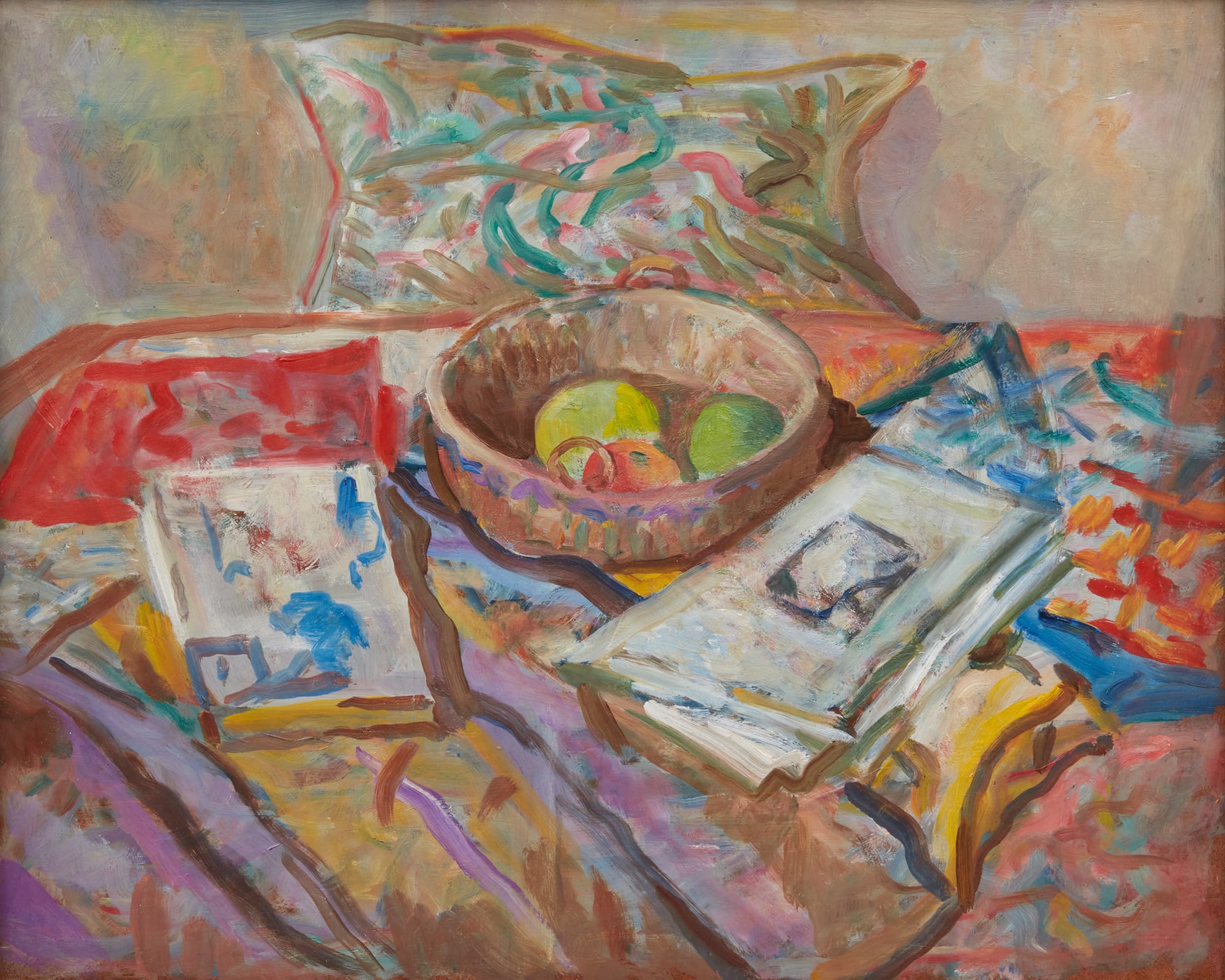

Frances Mary Hodgkins

-

Felix Kelly

-

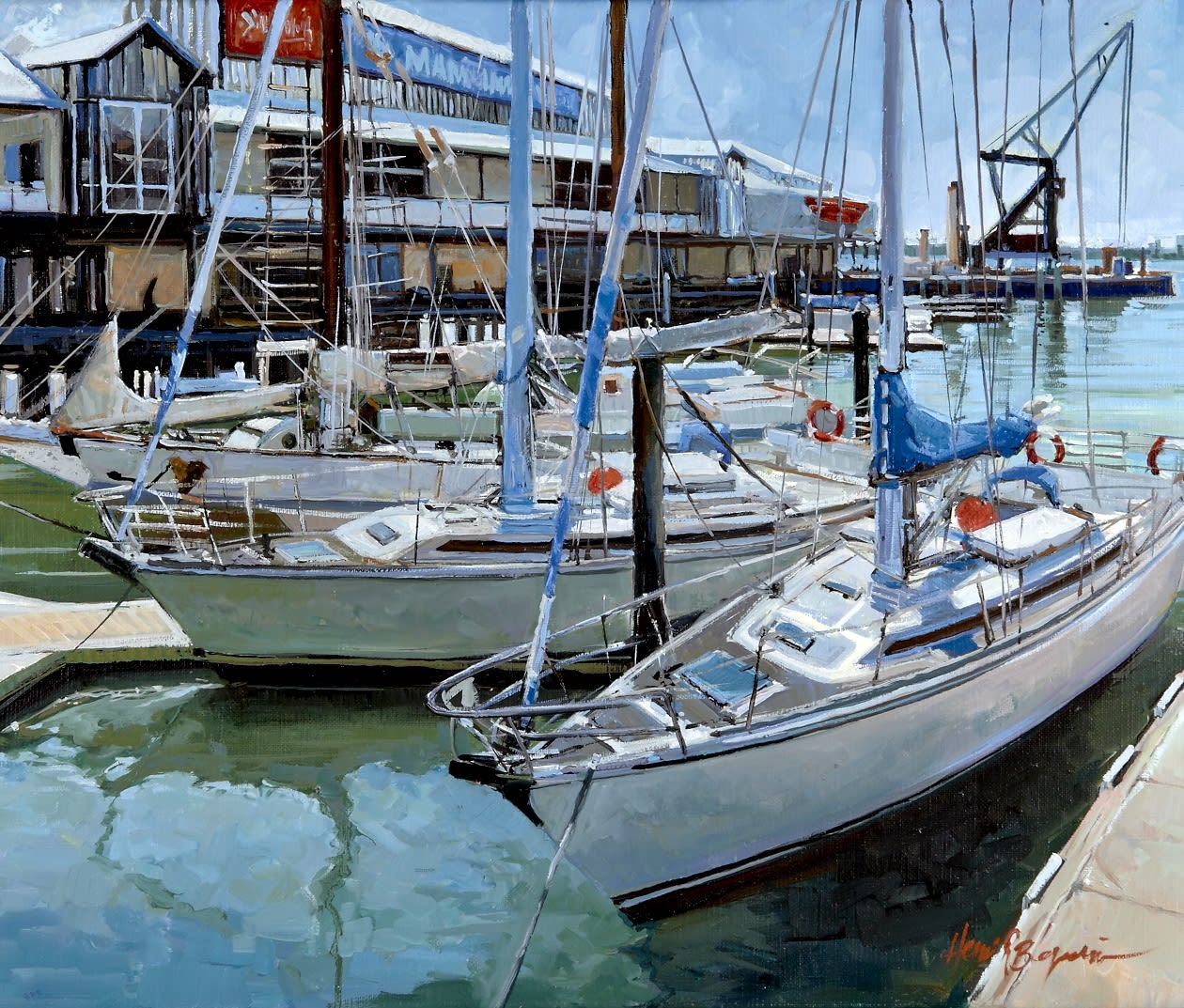

Henri Lepetit

-

Euan Macleod

-

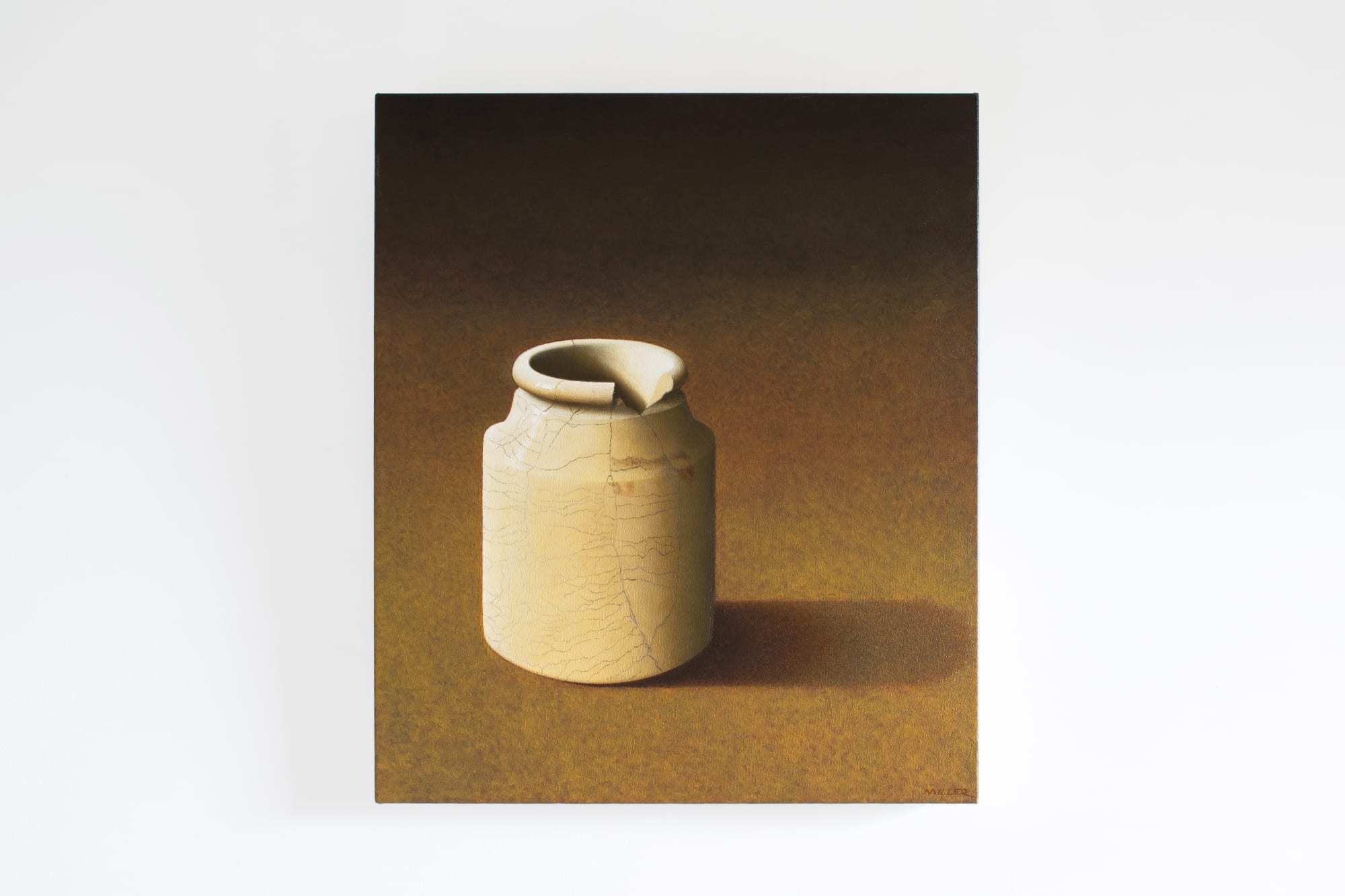

Francis McCracken

-

Peter McIntyre